The Women Are Persons Case

This case is a fascinating chapter from Canadian history—the "Women Are Persons" Case, more formally known as the Persons Case. In legal circles, it is cited as Edwards v. Canada (Attorney General). This story is about the fight for women's recognition and equality under the law, illustrating the interplay between politics, law, and society over time.

Today, we delve into a fascinating chapter from Canadian history—the "Women Are Persons" Case, more formally known as the Persons Case. In legal circles, it is cited as Edwards v. Canada (Attorney General). This story is about the fight for women's recognition and equality under the law, illustrating the interplay between politics, law, and society over time.

The case revolves around constitutional law, specifically the interpretation of the British North America Act of 1867, which established Canada as a country. This act, renamed the Constitution Act in 1982, is Canada's constitution.

The case was decided in 1929 by the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom, but the events leading to this decision began over a decade earlier.

In 1916, Canada (then known as the Dominion of Canada) was still part of the British Empire. It had autonomy to govern itself internally but was still subject to the control of the Empire in matters of foreign affairs and war. It would not be until 1931, with the British Parliament enacting the Statute of Westminster, that Canada would gain complete legal control over its foreign affairs and defence. In 1916, Canada was midway through World War I, contributing hundreds of thousands of soldiers to fight for the Empire.

In that same year, Emily Murphy began serving as a police magistrate in Edmonton, Alberta. She was appointed by Alberta's government to handle cases involving women and juveniles, becoming the first female judge in Canada and the British Empire.

At that time, women's roles were heavily constrained by both social norms and law. They were barred from voting in most of Canada and faced many other legal barriers. While progress was being made, it was inconsistent and took decades. For instance, although many women gained the right to vote in federal elections through legal amendments in 1917 and 1918, Quebec didn't allow women to vote in provincial elections until 1940, and federal and provincial voting rights for women from certain ethnic groups were only fully recognized between 1948 and 1960.

Interestingly, women had only been allowed to become lawyers within the previous two decades. Consequently, Emily Murphy’s appointment as a judge in 1916 garnered significant attention, not all positive.

An anecdote from Emily Murphy’s first day in office illustrates the resistance she faced. On that day in 1916, she reportedly had a lawyer named Harry Robertson appear before her, defending a client. He argued that under common law, women couldn't hold public office as they weren't considered "persons." He claimed this made Emily Murphy's appointment invalid. Magistrate Murphy dismissed his argument and ruled against his client.

After the case, Emily Murphy consulted with her brother, a judge in Ontario. She learned there was a legal foundation to Robertson’s claim: under the English common law system prevailing in Canada and throughout the British Empire, legal precedent did stipulate that women could not hold public office. However, times were beginning to change, and some governments in the Empire—including the provincial government of Alberta—had decided to look past this legal tradition and appoint women to public office regardless.

The argument that women were not within the legal definition of “persons” would keep coming up. Shortly after Emily Murphy’s appointment, another woman named Alice Jamieson was appointed as a magistrate in Alberta. A lawyer named Mackinley Cameron, representing a client in her court, made the same claim Robertson had before. He argued that Jamieson was “incompetent” to hold the office of magistrate and could not try his client because women were not persons under the law. Like Murphy, Jamieson disregarded this assertion and proceeded to try and convict his client.

However, unlike Robertson, Cameron did not drop his argument. He appealed his client’s conviction, arguing the verdict was invalid because the judge was not competent to hold office. The appeal was heard in 1917 by Justice David Scott of the Alberta Supreme Court, who, despite his doubts about a woman serving as a magistrate, upheld Jamieson’s decision.

The issue arose again in 1921 when Alberta created an appellate division to its Supreme Court. The statute creating the appellate division allowed past decisions to be appealed, and Cameron took this opportunity to challenge his client’s 1917 conviction once more. Justice Charles Allen Stuart of the Alberta Supreme Court’s new appellate division upheld women’s ability to hold office, dismissing Cameron’s arguments more forcefully than Justice Scott had. Stuart noted that the common law could evolve to reflect new societal conditions, such as the changing status of women. He stated, “If the common law rests on common sense, then there can be no bar to women in the public life of Alberta.”

Around this time, prominent Canadian women advocating for gender equality began to focus on the Canadian Parliament. The Parliament had two houses: the elected House of Commons and the appointed Senate, modeled on the British House of Lords. With recent amendments allowing women to vote and run in federal elections, the first woman was elected to the House of Commons in 1921. Now, there was much discussion about appointing the first woman to the Senate.

The Montreal Women’s Club proposed Emily Murphy as Canada’s first female senator. Not only was she Canada’s first female judge, but she was also a respected journalist and writer. And her recent book, “The Black Candle,” about the narcotics trade in Canada, had gained significant attention.

Despite this, the federal government claimed that appointing a woman to the Senate would violate section 24 of the British North America Act, which specified that a senator had to be a qualified “person.” The government argued that women were not included in this definition.

Years went by until, in 1927, advocates for a woman in the Senate decided to bypass the politicians and take the question of whether women were legally “persons” under the British North America Act to the courts. At that time, there was a section in the Supreme Court Act that allowed a group of five or more citizens to submit a petition asking for an advisory opinion from the Supreme Court of Canada on any provision of the British North America Act. Therefore, it was decided that a group of five prominent Canadian women ought to make use of this legal mechanism to put the federal government’s interpretation of the Act to the test and get an answer from the country’s highest court on whether women were qualified to hold high office or not.

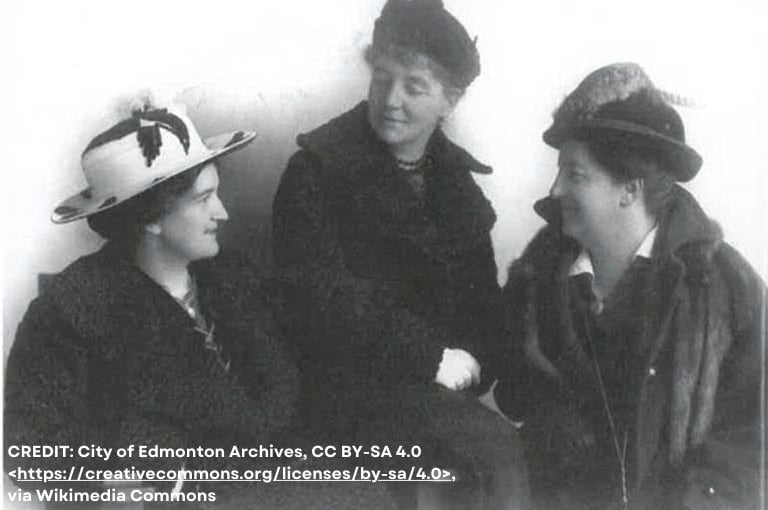

To that end, Emily Murphy and four other prominent advocates for women’s rights gathered and put pen to paper in the summer of 1927. The four others, in addition to Murphy, were Henrietta Muir Edwards, Nellie L. McClung, Louise C. McKinney, and Irene Parlby. Together they would eventually come to be known in Canadian history as the Famous Five.

These five women drafted a petition asking for an interpretation of the meaning of the term “person” in Section 24 of the British North America Act and sent it to the federal government in Ottawa. The petition wound its way through the various government channels and eventually, in March of 1928, the question came up for a hearing before the Supreme Court of Canada.

Presenting the case for the five women, and arguing that women were legally persons and eligible for membership in the Senate, was Newton W. Rowell, a nationally renowned lawyer from Toronto, as well as a well-connected politician who had held high office. He empathized with the cause of advancing women’s place in society and shared common ground with the five on other points as well; for example, both he and Nellie McClung were vocal opponents of alcohol.

Arguing the federal government’s case in opposition to Rowell was Lucien Cannon, Solicitor General of Canada. He continued to proclaim that, when the British North America Act had been enacted in 1867, the intention of the drafters had been to exclude women from the meaning of the word “person.” The understanding of the word at the time was that it applied only to men, and it was not open to be changed now, unless the entire Act was amended; and that could only be done by the Parliament of the United Kingdom since it was they who had enacted it in the first place.

Additionally, the provincial government of Quebec had been granted intervenor status in the hearing and had sent their own representative to express their view. Eugene Lafleur, Deputy Minister of Justice for Quebec, joined the federal government in declaring that it was clear that women could not be in the Senate. At one point, he asked, “How could women who had entered married life, and thereby owed obedience to their husbands, exercise the powers of Senator?”

After receiving the submissions and hearing the arguments from the various legal counsel, the justices of the Supreme Court retired to consider their decision. Weeks went by. Then, on April 20th, 1928, the court announced its judgment. It had found, by unanimous agreement of all six justices, that women were not “persons” within the meaning of Section 24 of the British North America Act and therefore could not be appointed to the Senate.

This was a disheartening setback to the Famous Five, but they were not yet defeated due to an interesting feature of the Canadian legal system that existed at the time. Since Canada was still a part of the British Empire, the Supreme Court of Canada was not the highest court in the Canadian legal system. That honour rested with a body known as the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council located in faraway London, the capital of the British Empire.

Technically speaking, under the British system of justice, the monarch was the fount of justice and the highest judicial authority, and so they were the final possible stop for all appeals in the Empire. However, the Judicial Committee was a body of lawyers and judges who served to advise the British monarch on legal matters. Therefore, the committee would receive the appeals on the monarch’s behalf and consider them, and then advise the sovereign on what they believed the correct decision was; and by tradition and custom the monarch would always follow this advice.

The Famous Five and their legal counsel would take their case to this final arbiter of justice in the Canadian and British legal systems, hoping that it might choose to reverse the loss suffered before the Supreme Court of Canada.

Once the appeal was filed with the Judicial Committee in London, the five women and their counsel had to wait for some months before their case was heard. The committee was dealing with eight appeals from Canada and theirs was eighth in line. Finally, in July 1929, their case’s allotted time came up and, although waiting might have been frustrating for the Famous Five, it might have just done their case some good.

As fate may have it, there had been a change in government in the United Kingdom. The Labour Party had won the latest elections and formed a new administration, and the Labour Prime Minister had just appointed Viscount John Sankey as the new Chief Justice to preside over the Judicial Committee. Sankey was a progressively minded legal thinker and former politician and was just the sort of person who would look favourably on advancing the status of women.

There were several days where the opposing legal counsel presented their cases once again, this time before the Judicial Committee instead of the Supreme Court of Canada. After they were finished, the board of five judges, headed by Viscount Sankey, retired to their chambers to discuss and deliberate.

It would then take months before the committee announced its decision, but when it was finally proclaimed on October 18th, 1929, it was welcome news to the Famous Five. The Judicial Committee had agreed that the Supreme Court’s decision was incorrect, and that the word “person” as found in the British North America Act did include women. There was no legal barrier to women serving in the Senate.

The judgment of the committee was delivered eloquently by Viscount Sankey, who rejected the Supreme Court’s finding that it was bound by the historical understanding of the word “person” that had prevailed during the time when the Act was written. He dismissed the idea that new interpretations of the law could not be developed over time to meet the changing needs of changing times, and declared that the British North America Act was a living tree that could, subject to certain limits, grow into whatever the nation of Canada needed it to be.

In the written judgment for the committee, Sankey wrote: “The exclusion of women from all public office is a relic of days more barbarous than ours.” Later, he also wrote: “The word ‘person’ may include members of both sexes, and to those who ask why the word should include females, the obvious answer is why should it not.”

The Famous Five had won and a legal pathway had been cleared for women to enter the Senate of Canada. And that would occur shortly thereafter, with Cairine Wilson being sworn in as the first female senator on February 15th, 1930.

There was disappointment amongst some that the office did not go to Emily Murphy or one of the others in the Famous Five. In fact, none of them ever were appointed to the upper chamber of Canada’s Parliament. Regardless, they had achieved a legal victory that would open the door to higher office for countless women in ensuing generations and they have been commemorated in a number of ways. There are statues of them on Parliament Hill in Ottawa, Canada, they were depicted on the Canadian $50 bill for a time and October 18th has been named Persons Day in their honour.

Today, looking back, some are more critical of the legacy of the Famous Five. It has been noted there were some amongst their number who had objectionable views on race and immigration. As well, it has been pointed out that several of them were in favour of eugenics and forced sterilization.

These things are all true and the problematic aspects of these five women should not be overlooked, but history and figures in history are complicated. We must acknowledge the good done by persons along with the bad. As was stated by Dr. Rebecca Sullivan of the University of Calgary when interviewed by CBC for a story on the Famous Five, “We have to be mindful. Our histories don't have to be 100 per cent celebratory any more than they have to be 100 per cent critical. Our histories are complicated.”

SOURCES:

Alberta Champions Society in Recognition of Community Enrichment. (n.d.). Alice Jane Jukes Jamieson (1860 to 1949). Alberta Champions. Retrieved June 16, 2024 from https://albertachampions.org/Champions/jamieson-alice-jane-jukes-1860-1949/

Bell, D. (2019, October 18). 'Our histories are complicated': Famous Five fought a good but imperfect fight. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/calgary/famous-five-fought-good-imperfect-fight-1.5325290

Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. (2018, June 21). The Famous Five and the 'persons' ruling of 1929. CBC Archives. https://www.cbc.ca/archives/the-famous-five-and-the-persons-ruling-of-1929-1.4669584

Cashman, T. (2014, July). The Persons Case in 65 Minutes Preceded by the Persons Case in 200 Words [Presentation]. Canada History Week July 2014 at the Provincial Archives of Alberta. https://provincialarchives.alberta.ca/sites/default/files/2020-05/The%20Persons%20Case%20by%20Tony%20Cashman.pdf

Collin, S. (2022, August 24). Canadian Women in the Legal Profession: From Non-‘Persons’ to Chief Justices. Best Lawyers. https://www.bestlawyers.com/article/canadian-women-legal-profession/4027

CPAC. (2014, March 17). Did You Know? - The Famous Five and the Persons Case [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=if_pyx5dm9Y

de Bruin, T. & McIntosh, A. (2020, November 10). Agnes Macphail. In The Canadian Encyclopedia. (Original work published April 1, 2008). Retrieved June 16, 2024 from https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/agnes-macphail

de Bruin, T., Cruickshank D.A. & McIntosh, A. (2020, November 6). Persons Case. In The Canadian Encyclopedia. (Original work published February 7, 2006). Retrieved June 16, 2024 from https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/persons-case

Edwards v. Canada (Attorney General), 1929 CanLII 438 (UK JCPC). https://canlii.ca/t/gbvs4

Elections Canada. (n.d.a). First Nations Peoples and the Right to Vote Case Study. Elections and Democracy! Retrieved June 9, 2024 from https://electionsanddemocracy.ca/voting-rights-through-time-0/first-nations-and-right-vote-case-study.

Elections Canada. (n.d.b). Inuit and the Right to Vote Case Study. Elections and Democracy! Retrieved June 9, 2024 from https://electionsanddemocracy.ca/voting-rights-through-time-0/inuit-and-right-vote-case-study

Elections Canada. (n.d.c). A Brief History of Federal Voting Rights in Canada. Elections and Democracy! Retrieved June 9, 2024 from https://electionsanddemocracy.ca/voting-rights-through-time-0/brief-history-federal-voting-rights-canada

Elections Canada. (n.d.d). Japanese Canadians and the Right to Vote Case Study. Elections and Democracy! Retrieved June 9, 2024 from https://electionsanddemocracy.ca/voting-rights-through-time-0/case-study-1-japanese-canadians-and-democratic-rights

Elections Canada. (n.d.e). Women’s Right to Vote Case Study. Elections and Democracy! Retrieved June 9, 2024 from https://electionsanddemocracy.ca/voting-rights-through-time-0/case-study-2-womens-right-vote

Farr, D.M.L. & McIntosh, A. (2020, May 1). Judicial Committee of the Privy Council. In The Canadian Encyclopedia. (Original work published February 7, 2006). Retrieved June 17, 2024 from https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/judicial-committee-of-the-privy-council

Jackel, S., Cavanaugh, C., Marshall, T. & McIntosh, A. (2020, November 20). Emily Murphy. In The Canadian Encyclopedia. (Original work published April 1, 2008). Retrieved June 16, 2024 from https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/emily-murphy

Marshall, T. (2023, October 11). Persons Case. In Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/event/Persons-Case

McIntosh, A., Hillmer, N. & Foot, R. (2020, April 29). Statute of Westminster, 1931. In The Canadian Encyclopedia. (Original work published February 7, 2006). Retrieved June 16, 2024 from https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/statute-of-westminster

Morton, D., de Bruin, T., Foot, R. & Gallant, D. (2023, November 30). First World War (WWI). In The Canadian Encyclopedia. (Original work published August 5, 2013). Retrieved June 16, 2024 from https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/first-world-war-wwi

Mussett, B. (n.d.) Chinese Get the Vote. British Columbia – An Untold History. Retrieved June 9, 2024 from https://bcanuntoldhistory.knowledge.ca/1940/chinese-get-the-vote

Reference re meaning of the word “Persons” in s.24 of British North America Act, 1928 CanLII 55 (SCC), [1928] SCR 276. https://canlii.ca/t/fslfx

The Constitution Act, 1867 [British North America Act, 1867], 30 & 31 Vict, c 3. https://canlii.ca/t/ldsw

VLOG VERSION